How to Turn Food Waste Into Compost and Gas in New York

New Yorkers already have blue and green bins for recycling glass, metal, paper and plastic. But now brown bins for organic waste are starting to appear all over the city. These plastic totems are part of the city’s multimillion-dollar campaign to cut down on greenhouse gas emissions and reliance on landfills, and to turn food scraps and yard waste into compost and, soon, clean energy.

About 14 million tons of waste are thrown out each year. It costs the city almost $400 million annually just to ship what it collects from homes, schools and government buildings (by rail, barge or truck) to incinerators or landfills as far away as South Carolina. (In addition, dozens of private companies put trucks on the road to take away refuse from office buildings and businesses.)

The largest single portion of the trash heap is organics, or things that were once living. That apple core, that untouched macaroni salad, that slice of pizza and the greasy paper plate it was served on are heavy with moisture, which makes shipping expensive. As they decompose, they release methane, a greenhouse gas.

New York’s residential organics collection program is already the largest in the country: More than a million residents in parts of all five boroughs have curbside service. By the end of next year, officials say, all city residents will have a way to recycle their food scraps and other leaf and yard waste.

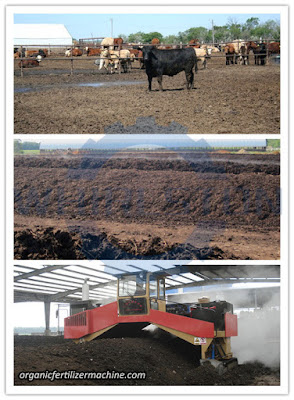

The composting process employs billions of microorganisms to break down organics into the essential component of soil called humus, which requires compost turner machine to make compost faster and better.Grass clippings, food scraps and coffee grounds (“greens”) are mixed with dry leaves or branches (“browns”), spread into piles and churned by hand or machine to promote decay. It can take six to nine months for the materials to decompose completely. Compost is known to farmers as “black gold” because turning compost into organic fertilizer can help plants take root and prevents soil erosion. The earth has been recycling organics for billions of years. But according to Jean Bonhotal, the director of the Cornell Waste Management Institute, humans have interrupted that circular system by entombing valuable nutrients in landfills and relying on chemical fertilizers. So it is necessary to compost wastes for organic fertilizer production line.

The composting process employs billions of microorganisms to break down organics into the essential component of soil called humus, which requires compost turner machine to make compost faster and better.Grass clippings, food scraps and coffee grounds (“greens”) are mixed with dry leaves or branches (“browns”), spread into piles and churned by hand or machine to promote decay. It can take six to nine months for the materials to decompose completely. Compost is known to farmers as “black gold” because turning compost into organic fertilizer can help plants take root and prevents soil erosion. The earth has been recycling organics for billions of years. But according to Jean Bonhotal, the director of the Cornell Waste Management Institute, humans have interrupted that circular system by entombing valuable nutrients in landfills and relying on chemical fertilizers. So it is necessary to compost wastes for organic fertilizer production line.

About 14 million tons of waste are thrown out each year. It costs the city almost $400 million annually just to ship what it collects from homes, schools and government buildings (by rail, barge or truck) to incinerators or landfills as far away as South Carolina. (In addition, dozens of private companies put trucks on the road to take away refuse from office buildings and businesses.)

The largest single portion of the trash heap is organics, or things that were once living. That apple core, that untouched macaroni salad, that slice of pizza and the greasy paper plate it was served on are heavy with moisture, which makes shipping expensive. As they decompose, they release methane, a greenhouse gas.

New York’s residential organics collection program is already the largest in the country: More than a million residents in parts of all five boroughs have curbside service. By the end of next year, officials say, all city residents will have a way to recycle their food scraps and other leaf and yard waste.

So how will it work?

- Picking Up

New York’s dense, vertical landscape makes collection a labyrinthine endeavor. Creating all-new routes just to fetch organics would be expensive and snarl traffic. The city is finding ways to modify existing routes, using trucks with separate compartments for trash and organics.

- Making Compost

The composting process employs billions of microorganisms to break down organics into the essential component of soil called humus, which requires compost turner machine to make compost faster and better.Grass clippings, food scraps and coffee grounds (“greens”) are mixed with dry leaves or branches (“browns”), spread into piles and churned by hand or machine to promote decay. It can take six to nine months for the materials to decompose completely. Compost is known to farmers as “black gold” because turning compost into organic fertilizer can help plants take root and prevents soil erosion. The earth has been recycling organics for billions of years. But according to Jean Bonhotal, the director of the Cornell Waste Management Institute, humans have interrupted that circular system by entombing valuable nutrients in landfills and relying on chemical fertilizers. So it is necessary to compost wastes for organic fertilizer production line.

The composting process employs billions of microorganisms to break down organics into the essential component of soil called humus, which requires compost turner machine to make compost faster and better.Grass clippings, food scraps and coffee grounds (“greens”) are mixed with dry leaves or branches (“browns”), spread into piles and churned by hand or machine to promote decay. It can take six to nine months for the materials to decompose completely. Compost is known to farmers as “black gold” because turning compost into organic fertilizer can help plants take root and prevents soil erosion. The earth has been recycling organics for billions of years. But according to Jean Bonhotal, the director of the Cornell Waste Management Institute, humans have interrupted that circular system by entombing valuable nutrients in landfills and relying on chemical fertilizers. So it is necessary to compost wastes for organic fertilizer production line.- Making Biogas

Like the human stomach, anaerobic digestion facilities use microbes to break down organics into biogas, which is primarily methane and carbon dioxide. The same way humans chew to accelerate digestion, machines grind organics into a slurry the consistency of a milkshake, which is fed into a large, airtight tank heated to about 100 degrees, called a digester. What comes out are biogas and a mix of water and solids. The biogas must be refined before it can be put into a utility’s natural gas pipeline, or used as fuel for trucks and buses. It can also be converted to electricity and heat to power homes and businesses.

Remark: this article comes from nytimes.com and pic is made by Joren Cull.

Comments

Post a Comment